EEUU: Managing potato diseases in storage

High-tech solutions can help to find problems before they’ve become critical

Whether it’s fresh or processing potatoes, any issue in storage needs to involve partnership with your end-user,” says Mary LeMere, an agronomy manager with McCain Foods based in Wisconsin.

LeMere was at Manitoba Potato Production Days in Brandon, Man. January 24 to 26 to deliver “lightning advice” on three key topics — managing late blight in storage, the impact of pile height on potato quality, and tips for using FLIR cameras to detect issues in the pile.

All three topics are highly relevant for Manitoba producers after a year that saw above-average volumes heading into storages around the province.

But LeMere says a common theme is the need to communicate with end-users, who have a stake in maintaining healthy spuds from the field to the plate.

Managing disease in storage

“Manitoba did have late blight in the field last summer,” said LeMere in an interview. “Sometimes infections in the field can be mild, and then you’ll be in the middle of storage and you’ll see defect reports showing up. What do you do?”

The first step, LeMere says, is to control the environment, then to communicate the discovery with the end-user. After this, producers should assess the level of infection and risk, monitor the progression of the disease, and sanitize any facilities or equipment that have come into contact with infected potatoes.

“Keep an eye on it if this happens, and sell the potatoes as quickly as you can,” LeMere said.

ADVERTISEMENT

The risk of disease spreading in storage is influenced by many factors, but pile height is one producers sometimes overlook.

Stacking pile heights higher than the building is designed for can lead to an overall reduction in the air volume available per hundredweight of potatoes. It can also reduce the buffer zone at the top of the pile, which can result in condensation collecting on the ceiling, leading to disease risk.

LeMere says an added factor is that storage buildings are pressurized, meaning everything functions well with a certain level of static pressure. “If you have more than the normal amount of potatoes in your building and not enough headspace above the pile, your fans will work harder and have less output,” she said.

Some years, producers can get away with overstocking storages, but in bad years this can result in rot and breakdown.

And there’s more at risk than disease: chances of potatoes developing pressure bruising increase in overstocked storages, particularly when producers are used to running storages on the dry side, LeMere says.

ADVERTISEMENT

Some producers shut off humidity when potatoes go into storage because the spuds respirate during the harvest period, producing a lot of moisture.

“The problem with turning off the humidity all the way is that that’s the time period when they are losing the most moisture — they have open skin surfaces and wounds, which lose moisture at a higher rate, and once you lose that moisture you can’t get it back,” LeMere said.

“What’s recommended at harvest is that when potatoes are producing 100 per cent humidity on their own, leave the system on standby so the relative humidity system kicks in as the humidity drops. Don’t turn it off completely for months at a time.”

Put technology to work

Producers aren’t without gadgets to help them assess potential risks in the pile, LeMere says.

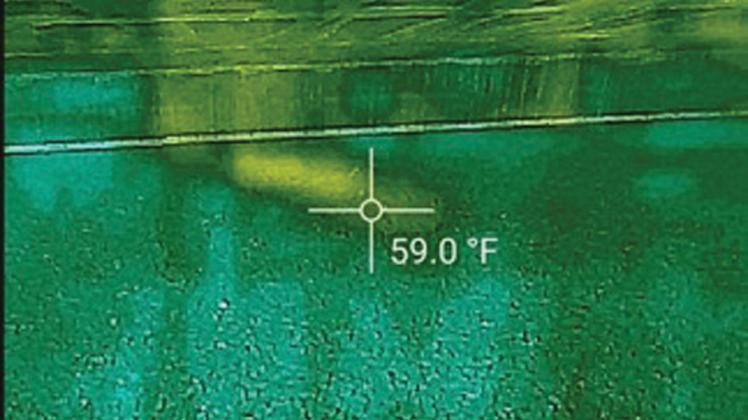

McCain has started providing field and agronomy staff with tiny FLIR One cameras that attach to the bottom of their smartphones (iPhone or Android).

The thermal imaging infrared cameras — which have traditionally been used by heating, ventilation and air conditioning specialists and electricians — pick up heat readings, so McCain has put them to work looking for hot spots in potato piles.

“We’ve found buildings with gaps in their ventilations, where potatoes between ventilation pipes are getting warmer. We’ve found hot spots before they’ve developed a smell or started to rot — so we can pre-emptively stop the problem before it reaches physical breakdown,” LeMere said.

Producers can use the cameras from the start of harvest, measuring the temperature of loads going into storage, assessing temperature differences day to day.

“We’ve used it for making loading and unloading decisions: if you’re unloading and there’s some rot on the face of the pile, you can call the end-user to come get the top ones,” she said. “Then you can use the camera to check whether you’ve got it all.”

In the U.S., the camera retails for around US$250, and in Canada it costs around $330, says LeMere.

The camera isn’t a miracle worker — it detects heat coming off the surface of the pile, but not deep inside. It’s simply one more tool that can help producers pick up on storage issues.

As always, another solution is to reach out to the experts.

“Call me,” LeMere said. “I love talking to people about storage and potatoes, even if they’re not a McCain grower.”

Fuente: https://www.manitobacooperator.ca/crops/managing-disease-in-storage/